Point Clouds

Point clouds come from terrestrial lidar surveys, bathymetric sonar surveys, as well as 3D scanning and photogrammetry applications. As with most remote sensing techniques, the collected data tend to have some level of noise introduced by the system, along with data artifacts. This means that the data need to be cleaned, either by an algorithm or manually by a human. When it comes to point clouds used to produce navigational maps and other safety-critical applications, a human must always be included in the cleaning loop to edit and/or verify the data that is cleaned. Another common task is to annotate sections of a point cloud to separate things like buildings, navigational aids, tree canopy, and other objects of interest.

3D point clouds can be very challenging to view and manipulate on a 2D display. Point clouds are inherently a collection of single points distributed throughout a 3D space, and when viewed on a standard desktop screen, there is not much depth information that can be derived from the individual points, nor the point cloud as a whole. Increasing the visual weight of points by representing them as discs or squares can allow for binary depth cues like occlusion, but it is still very difficult to ascertain the relative distance between two occluding points; just that one point is closer to the viewer than the other. Motion parallax through scene movement can help to provide relative depth cues, but scene motion can pose significant challenges to editing and annotating points in the cloud.

Motion parallax and occlusion provide depth cues for point clouds

Point Clouds in VR

The best way to get strong depth information from a point cloud is through stereoscopic viewing. Previously, the easiest and most cost-effective way to do this would have been through using a stereoscopic 3D desktop display in a system like Fishtank VR . Now, 3D desktop displays are increasingly rare, and have been largely superceded by high-quality virtual reality (VR) headsets for viewing 3D content. In addition to stereoscopic viewing, VR headsets provide spatial tracking, so that subtle head movements can provide strong, natural motion parallax cues in addition to stereopsis. The result is a low-cost, easy-to-use, and visually compelling system for dealing with inherently three-dimensional data sets, and point cloud visualizations may be one of the biggest beneficiaries of the current wave of consumer-grade VR technology in this regard.

Bimanual Interaction

Yves Guiard developed the kinematic chaining model of bimanual actions in which the left and right hands form a kinematic chain and the non-dominant hand forms a frame of reference which the dominant hand can use for its movements. An example of this type of asymmetric action would be painting a figurine by holding it in one hand and painting fine details with the other.

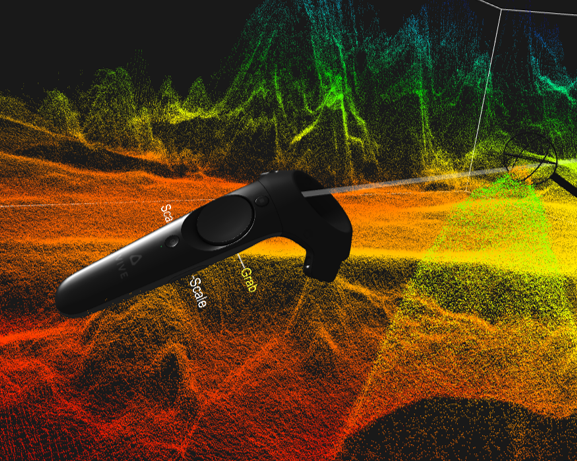

In our VR point cloud editor, we use the controller in the non-dominant hand to “grab” the dataset to directly reposition and reorient the point cloud, while the controller in the dominant hand uses an editing tool to flag points for removal (or annotation). These actions can be combined, as shown in the clip below, where the point cloud is manipulated with the left hand while the right hand simultaneously removes points.

Bimanual direct interaction with point cloud data

Point Cloud Tools

We have created a set of tools for and using the Unity real-time 3D development platform. You can find out more about these tools and download them in the Tools section .

The XRPCC Virtual Reality Point Cloud editing app

References

-

Stevens, A. H. and Butkiewicz, T. 2019. Faster Multibeam Sonar Data Cleaning: Evaluation of Editing 3D Point Clouds using Immersive VR. OCEANS 2019 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE, 2019, pp. 1-10.

doi: 10.23919/OCEANS40490.2019.8962793 -

Aygar, E., Ware, C. and Rogers, D. 2018. The Contribution of Stereoscopic and Motion Depth Cues to the Perception of Structures in 3D Point Clouds. ACM Trans. Appl. Percept. 15, 2, Article 9 (April 2018), 13 pages.

doi: 10.1145/3147914